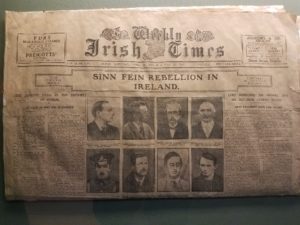

The Republic of Ireland has the mar of discrimination and disenfranchisement in its history. Catholics and Protestants battled for power in the 1600s. In the 1640s and 1680s, Catholics won significant authority over Protestants, with political power returning to Protestants in the early 1690s. However, many Protestants were in fear of a repeat of the 1640s and 1680s, leading to the passage of a number of laws disenfranchising Catholics, from about 1691 to around 1790, including precluding Catholics from sitting in parliament; requiring the registration of clergy; and restrictions on the freedom of Catholics to educate their children, to carry arms, to inherit, own, lease and work land, to trade and employ, to enter the major professions, and to vote. The bulk of these laws became known as The Penal Laws.

Ireland, much like the United States, was born out of common law. Also like the United States, prior legal opinions of higher courts are binding on the lower courts deciding new cases. There are civil and criminal courts in Ireland, also like the United States. Irish courts have trial and appellate courts, just as we do in the United States.

In Ireland there is also a constitutional legal right to criminal representation for the indigent. This right was afforded through the Criminal Justice Act of 1962. Just as in the United States, if you are criminally charged and cannot afford legal representation, the government must provide you with an attorney and foot the bill.

In Ireland this came about as a recognition by its Supreme Court that a defendant must be put on equal ground with the prosecution. In the criminal justice systems of both countries, a possible prison sentence is a trigger for this right. In both systems, the defendant must financially qualify for this representation (i.e., prove his or her indigency). In both systems, the seriousness of offense plays a role in determining the level of income that qualifies as indigent. And in both systems, the financial means of the parents of a juvenile are considered.

In Ireland, as in the State of Colorado, it is a crime to make a false statement about your financial income when applying for indigent counsel. In Ireland, the offense carries a possibility of a sentence of up to six months imprisonment. In the State of Colorado, there are two separate offenses which could be charged. The crime of False Information, which also carries the possibility of a sentence of up to six months imprisonment. However, in Colorado a person falsifying information as to income could also be charged with Attempt to Influence a Public Servant, which carries a possibility of up to six years in prison.

In Ireland, judges will make efforts at assigning the lawyer of the defendant’s choice if he or she participates in providing counsel to the indigent and is available, even though there is no absolute right to the lawyer of one’s choosing. If the court doesn’t grant the lawyer of one’s choosing, the judge must state the reason and allow the defendant to make another choice. In Colorado, however, no deference is given whatsoever to the desires of the defendant as to their court-appointed lawyer.

Once court-appointed counsel is provided in both Ireland and Colorado, this funding includes the funding of experts necessary for one’s defense. In both locations (in some cases), it will also include the cost of representation by two lawyers simultaneously.

At the time of this writing, Tripadvisor ranks visiting the Kilmainham Goal Museum in Dublin, Ireland, as the number one thing to do in Dublin.

This is the location where many leaders of opposition have been held, and some executed, throughout Ireland’s history.

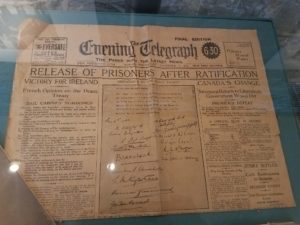

The Kilmainham Goal was the county jail and also housed prisoners of political significance. Convicts were also held there while awaiting exile to Australia.

The opening and closing of this facility coincided with the making and breaking of the union between Ireland and Great Britain. Today the Kilmainham Goal no longer operates as a jail and is instead a museum.

The Cork courthouse looks like any small, old courthouse you’d find in America, with creaking wood floors, regal benches for the judge, and a musty smell in the air. Though old, it bustles with modern Irish lawyers and their clients, meeting privately and with hushed voices in any available corner or nook outside of the courtrooms, exactly as is the practice in courthouses throughout the United States, including those in Colorado. Also, while modern technology has been added more recently to update the courthouse in Cork, it remains visibly old and striking in its appearance.